"I was put here to write, so I suppose that’s what I’ll continue to do."

An excerpt from my mini-interview for author Wendy C. Ortiz's "Mommy's El Camino"

Late last year, author and online friend Wendy C. Ortiz asked me to do a mini-interview for her newsletter “Mommy’s El Camino.” I’ve been reflecting lately on some of the feelings and memories that her questions stirred in me, and I wanted to share a few of them with y’all here (realizing I hadn’t done so back in August).

From Wendy:

“It’s hard to say just how long I’ve been aware of Kasai Richardson on the internet. I know it began with Twitter—seeing posts that I registered as straight-up truth, sometimes making me laugh, and more than once go, Oh, shit… in that way you might when you’re like, This truth is so real it hurts.

“So I’ve been aware of Kasai, and have felt some kind of long-distance fondness for making me laugh, see truth, and also, enjoy some fierce cat memes among his Instagram stories. Then I realized he had a stack, Rants Rants Revolution. And the posts I saw first were these. I mentioned them in a recommendation a few months ago, and/but they are timeless.

“As is my mini-interview practice, I asked Kasai to respond to three to five questions from a total of eight offered.”

Wendy: Take us on a walk through a place that gives you life.

Kasai: One place I truly know peace is the backyard of my parents’ home. The whole house really, but especially posted up in a patio chair on a warm spring day. It’s truly restorative. It wasn’t always the most peaceful place growing up for sure.

Their neighborhood was started in the early 20th century by Black professors as a response to the racist “No Blacks, No Jews” housing covenants of wealthy, white Baltimore neighborhoods such as Roland Park. When we moved there in 1995, the Cape Cod with peeling gray paint was overrun with scrap, greenery, and trash that my dad and I cleared out.

We each struggled growing up, in a number of ways. We’ve worked on ourselves to get to better places in our lives, through therapy, recovery, my dad finally getting his military benefits after being drafted into the Vietnam War, and my mother retiring from her federal job that was needed to provide for us but that also wore her down. Bit by bit my family has similarly worked on that house to make it more appealing and a more comfortable place to live.

The backyard transitions into a wooded area that descends into a nearby stream, and the trees let just the right amount of sunlight through. My audiophile father has set up outdoor speakers to complement the ever-present tunes in the house and on the front porch. Usually pumping old funk or R&B. I often go over there to bliss out when things feel overwhelming. As a family, we’re all in such a different place now, and the house is a different space as well. I’m grateful for the change on both fronts.

W: You're alone in the middle of the ocean. What are your thoughts?

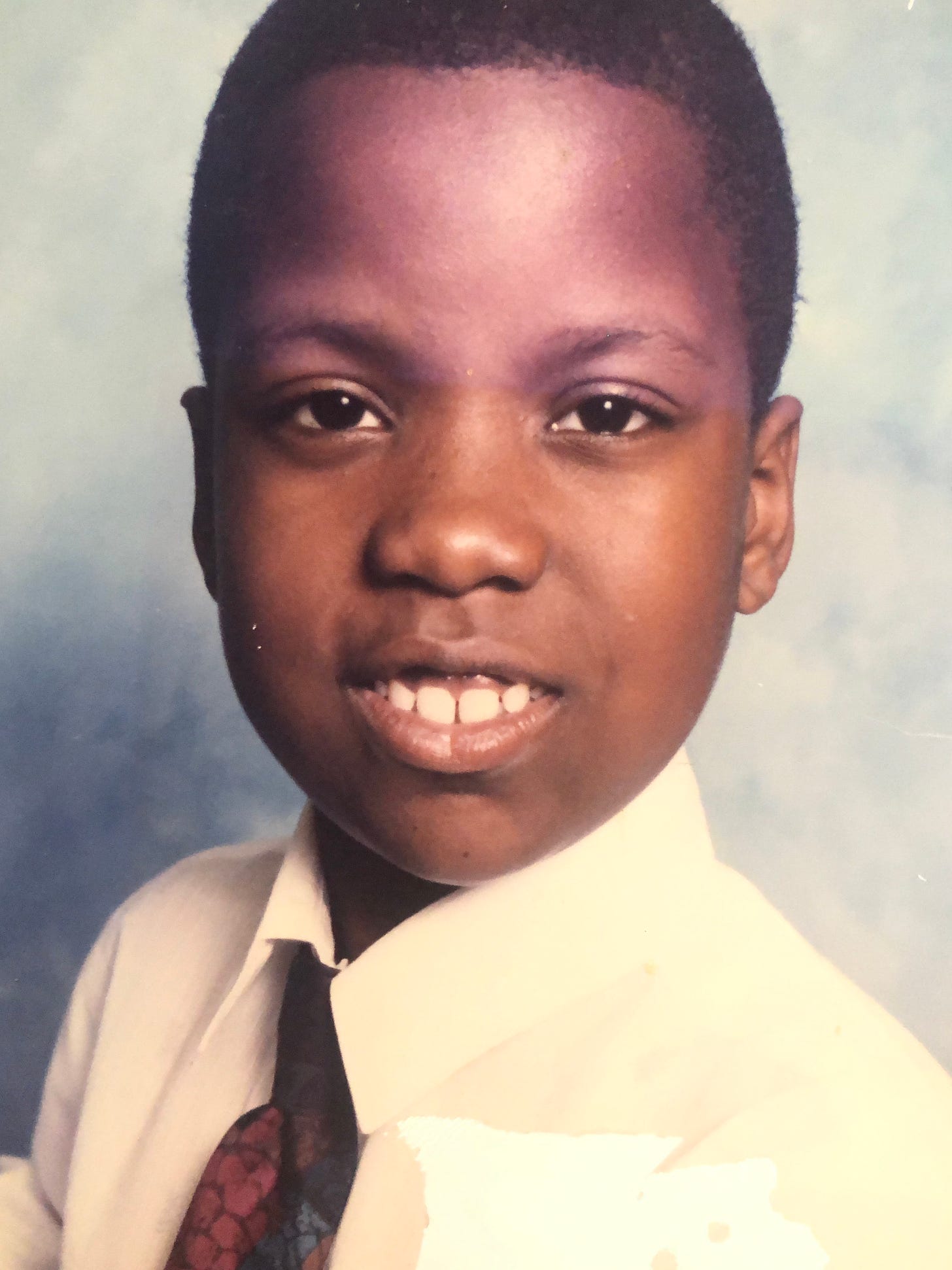

K: When I was 7, my first year at a private school in Baltimore whose only important claim is that John Waters also attended it, I went to a class party to mark the end of the school year. An old money family with a Dutch name and claimed “we were on the Mayflower” heritage hosted us. There was a pool adjacent to the castle-like main house. I don’t remember much about my walk towards the edge of it or what was going through my mind.

I took a step into the deep end and commenced drowning, as I hadn’t learned to swim like my classmates. I distinctly remember seeing angelfish swimming around me as the life left my body at the bottom of the pool. My friend’s father, whose family owned the property, saved me after who knows how long. I was the only Black kid in the class and my dad was Mr. Mom, tending to my baby sister and unaware of what was happening until it was over. Panicked white mothers judged him in the quiet yet unsubtle way white folks often do.

For a long time I resented him for not being the one to save me, and for not being as concerned in the aftermath as I felt he should’ve been. This was where I learned the pain of feeling abandoned, but I now know he was just scared out of his mind and doing the best he could while living with his own demons.

Later in life, in adolescence in particular, I had a phase of jumping into water and expecting people to save me. The height of my pre-recovery entitlement and death wish era I guess. I similarly stepped into the deep end of a lot of dangerous situations and behaviors for years. It’s a miracle I’m still here.

Something that’s also on my mind a lot, almost to the point of wanting to write about it, is that the rate of Black folks who know how to swim is lower than that of whites. Structural factors spanning many years, such as the segregation of pools, can be blamed in large part. I’m compelled to learn soon, but it hasn’t happened just yet.

Now though, alone and surrounded by shimmering ocean, I think about the tropical fish I saw at the bottom of that pool. The same fish my father owned when he worked at a tropical fish store way back when. Angelfish, cichlids, gouramis. Thrashing about in the depths, I regret putting off learning to swim still, but accept that there’s nothing that can be done to change that.

In brief flashes, I’m thinking about how I don’t feel abandoned anymore, even if I might be doomed. I’m at peace knowing I feel more content and more loved than I did that day in 1992 and for many days after it. I can go knowing I’ve been held and seen by so many, and that I actually did some good with my second shot at this thing.

W: What is your dream life (at night, asleep) like?

K: I’m an insomniac since way back, but my issue these last several years has been staying asleep more so than falling asleep, thanks to getting sober, untangling a lot of internal mess, and ending up with a sleep apnea diagnosis. For a long time, especially before I got sober in 2012, most of my dreams were stress dreams. Missing planes or trains. Teeth disintegrating in my mouth. Being attacked by knife-wielding villains or bitten by rabid animals. Loss of loved ones.

Even as a kid, my dreams were often big, cinematic joints that I could almost always remember in complete and colorful detail upon waking. Lately the cast is often played by people I went to school with who I haven’t seen since Bush was doing lines in the White House. Extras in the little movies my brain makes when I’m knocked out.

Sometimes the dreams feel catastrophic or like a portent of sheer disaster for me and everyone I care about. In others, I have 500 billion dollars and am endlessly baby-birding cash to people from all over the world. Occasionally, I have “drunk dreams,” where I drink or use drugs in my sleep and wake up thinking I’ve relapsed. Someone once described them as postcards from my disease, and I’ve taken them less seriously since.

Recently I woke up from an otherwise mundane dream that had me laughing into the forced air of my CPAP mask because of one of its characters: A nude mountain man snuggling a beehive in a state of unadulterated ecstasy, honeycomb in hand and covered in bee stings. “God damnit Bobby’s gotten into the apiary again!” someone shouted. Another had Mariska Hargitay, television’s Olivia Benson on Law And Order: SVU, showing me her yearbook while we were seated for dinner in a crowded New York restaurant.

I think a lot about the Black-White sleep gap, and how many of us in general are walking around completely drained thanks to this system we’re clinging on to.

And part of me wants my dreams to be this generative deal that serves as a wellspring for ideas for my writing, especially the fiction-writing part of my brain that I want to jumpstart back to life. But maybe it’s not that kind of party. I know generally people grow bored when discussing each other’s dreams, but I love sharing them. It’s another layer of someone that you get to discover, even if some of it is mundane or goofy.

To read the rest, peep and subscribe to Wendy’s Buttondown, "Mommy’s El Camino,” here.

Love you!

About Wendy:

Wendy C. Ortiz is the author of Excavation: A Memoir, Hollywood Notebook, and the dreamoir Bruja. Her work has been featured in the Los Angeles Times and the Los Angeles Review of Books. Her writing has appeared in The New York Times, BOMB Magazine online, FENCE, and elsewhere. Wendy is a parent and psychotherapist in private practice in Los Angeles, California.

Rants Rants Revolution is reader-supported. To receive new posts and support my future work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber. Thank you!